The IEEE Electrification magazine featured invited articles on hydrogen-electric aircraft technologies in the June 2022 issue. “Electric Propulsors for Zero-Emission Aircraft: Partially Superconducting Machines” by Samith Sirimanna, Thanatheepan (Theepan) Balachandran, Noah Salk, Jianqiao Xiao, Dongsu Lee, and Kiruba Sivasubramaniam Haran was highlighted on the front cover. All the authors are employed in Professor Haran’s company Hinetics, Powering the Future of Aviation, Aviation and Aerospace Component Manufacturing in Champaign, IL. Samith Sirimanna, Theepan Balachandran and Jianqiao (Peter) Xiao are currently students of Professor Haran; Dongsu Lee is his former post-doc; and Noah Salk, a PhD student at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, earned his BSEE at the University of Illinois and was a Research Assistant in Professor Haran’s Group from May 2019 through June 2020.

To learn more and read, please visit: https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn%3Ali%3Aactivity%3A6947320119505154048/?midToken=AQF_r414QxMFfQ&midSig=1OwC5VzB1Lfqk1&trk=eml-email_notification_digest_01-notifications-6-null&trkEmail=eml-email_notification_digest_01-notifications-6-null-null-1hu7mi%7El4xirejw%7E4g-null-voyagerOffline

For more on Hinetics, see https://www.linkedin.com/company/hinetics/?miniCompanyUrn=urn%3Ali%3Afs_miniCompany%3A18723799

Phil Krein – General Chair of the 2022 IEEE Transportation Electrification Conference and Expo, Asia-Pacific

ITEC Asia-Pacific 2022 will be held on the Zhejiang University (ZJU) International Campus, Haining, Zhejiang Province, China, from October 28–31, 2022. The conference covers all major topics in power electronics, electric machines, and power systems for transportation electrification. It addresses a variety of transportation systems such as electric vehicles, hybrid and plug-in hybrid vehicles, fuel cell vehicles, heavy-duty and off-road vehicles, rail, sea, undersea, air, and space vehicles.

Haining is located in northeast Zhejiang Province, in the Hangzhou Bay region of the Yangtze River Delta. It is famous for the Qiantang River tidal bore, leather shadow puppets, and early silk fabric. Today, it is a major producer of leather, textiles, solar panels, and automotive parts.

Professor Krein served as Executive Dean of Zhejiang University/University of Illinois Joint Engineering Institute (ZJU-UIUC) from 2015 through 2020, and since 2020 has been director of the Dynamic Research Enterprise for Multidisciplinary Engineering Sciences (DREMES), a unique umbrella for active collaborations among ZJO, Illinois, and the ZJU-UIUC in Haining, China. The enterprise explores fundamental global issues in human health, energy and environments, and sustainable manufacturing.

Information for this announcement was excerpted from https://www.itec-ap2022.com/ and https://zjui.illinois.edu/research/DREMES

Katherine A. Kim – PELS 2022 Honoree for Pioneering Educational Videos and Online Learning in Power Electronics

Dr. Kim is both a researcher and educator who is renowned for developing engineering lecture videos that she has shared publicly on YouTube since 2014. She posts the lecture videos she develops to her YouTube channel called “katkimshow” which has 76,000+ subscribers and some of her videos have over 430,000 views. To make her courses more accessible, she launched the website called Engineering Spark that provides additional resources on her courses, including quizzes and simulation problems. Many students and industry professionals alike have said that these videos and coursework have been invaluable to their studies.

Dr. Katherine A. Kim received the B.S. degree in Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) from the Franklin W. Olin College of Engineering in 2007. She received the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in ECE from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011 and 2014, respectively, where she was very active in the Power and Energy Conference at Illinois (PECI), see PECI 2022, pages 38–40. In PECI’s inauguration year (2010), she served as Registration Officer; in 2011 she was in charge of the Program and in 2012 served as Co-Director. In 2013 she served in Publications and in 2014 was in charge of Student Networking. She also innovated a workshop on presentation skills, including PowerPoint karaoke.

Katherine was an Assistant Professor of ECE at Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST), Ulsan, South Korea, from 2014–2018. Since 2019, she has been an Associate Professor of Electrical Engineering at National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan. For IEEE PELS, she served as the Student Membership Chair in 2013–2014, PELS Member-At-Large for 2016–2018, PELS Women in Engineering Chair in 2018-2020, and currently is the PELS Constitution and Bylaws Chair 2021–2022.

Announcement about this award is at https://www.ieee-pels.org/pels-news/721-congratulations-to-our-2022-pels-award-winners?highlight=WyJuZXdzIl0=

Annabelle Epplin selected for NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Pathways Electrical Engineering Internship

Annabelle began a six-month NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) Co-Op January 2022 in Greenbelt, Maryland, as a Pathways Electrical Engineering Intern working in the Environmental Test Engineering and Integration branch. This area is comprised of multiple testing groups in the fields of space simulation, structural dynamics, and electromagnetic interference (EMI). She conducted several EMI, electromagnetic compatibility, and magnetics tests on spacecraft, ranging from a small box-level test to a full self-compatibility test, and was exposed to a variety of interesting concepts and ideas.

EMI engineers at GSFC are responsible for a variety of tasks related to the EMI tests, including supporting personnel in selecting a test procedure, brainstorming ideas to safeguard that testing is optimized for each project, and ensuring that testing runs smoothly. Each GSFC project is unique, from the newly launched James Webb Space Telescope to the upcoming Earth/ocean-observing PACE satellite (Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, Ocean Ecosystem). While testing is based on both predetermined NASA and military standards, tests can be adjusted to suit the design. The main EMI tests can be categorized into four groups: conducted emissions, conducted susceptibility, radiated emissions, and radiated susceptibility. Emissions testing consists of using hardware such as EMI test receivers and antennas (for radiated emissions) in combination with software such as EMC32 and TILE! to measure signals being produced by the DUT (device under test). The goal of emissions testing is to confirm that the DUT produces no signals that could interfere with other equipment on the spacecraft. Susceptibility testing includes delivering a known signal to the DUT and making certain there is no interference with the DUT performance.

Annabelle feels she has gained technical knowledge and problem-solving abilities that will benefit her as a student and researcher. She has learned about top-of-the-line hardware, comprising EMI test receivers, signal generators, oscilloscopes, antennas, and amplifiers, and gained practical experience with software, such as EMC32, TILE!, Python, and MATLAB. She has improved her soldering skills and, as of this report (with two months remaining for the internship), was prototyping a circuit for an upcoming test on a piece of spacecraft hardware. In preparation, Annabelle created a test procedure that provided the method and steps to be used during the test based on the project EMI plan provided. With the assistance of a technician, she was to help run the test.

With a variety of new engineering concepts under her belt, both from the EMI group and from project personnel, Annabelle feels she has gained confidence as an engineering student. She feels that she has become more independent as a future engineer and is grateful for the University of Illinois and the Grainger CEME Undergraduate Research and Leadership program for allowing her this experience.

This piece was excerpted from “NASA GSFC Co-Op Report,” Spring 2022, by Annabelle Epplin.

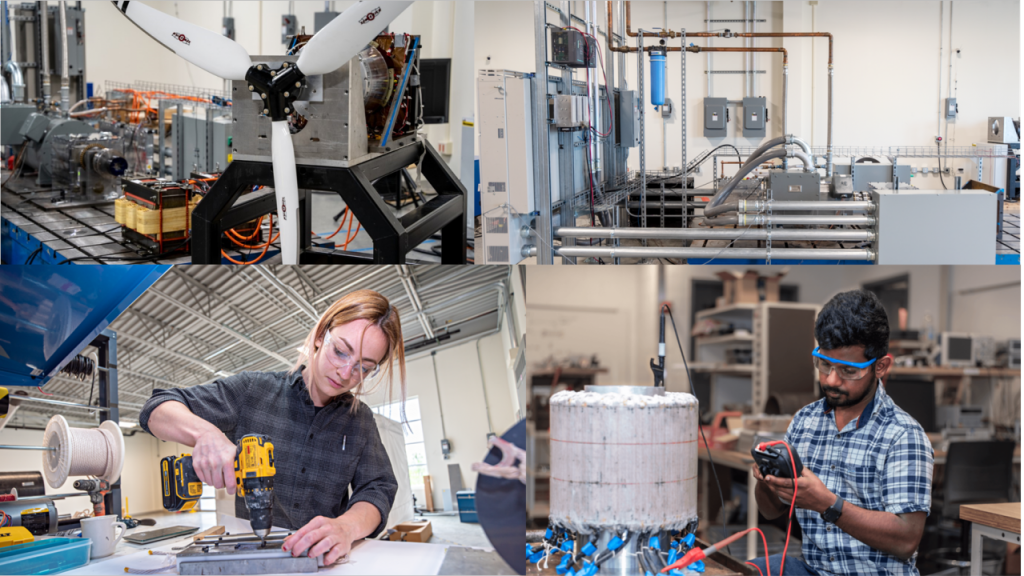

POETS Director’s Company Hinetics Awarded $5.7M of the More than $10M to POETS Faculty to Develop Clean Energy Technologies

Three out of the 68 research and development projects nationwide aimed at developing disruptive technologies to strengthen the U.S. advanced energy enterprise were awarded to POETS faculty, including Professor Kiruba Haran.

Led by the Department of Energy’s Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, the OPEN 2021 program prioritizes funding high-impact, high-risk technologies that support novel approaches to clean energy challenges.

Professor Haran’s startup company, Hinetics, will lead an OPEN 2021 project, Cryogen-fRee Ultra-high fIeld Superconducting Electric (CRUISE) Motor, which was awarded $5.7 million. The company, alongside UIUC and POETS researchers, will develop and demonstrate a high-power density electric machine to enable electrified aircraft propulsion systems up to 10 MW and beyond. Hinetics’ technology uses a superconducting machine design that eliminates the need for cryogenic auxiliary systems yet maintains low total mass. The concept features a sub-20 K Stirling-cycle cooler integrated with a low-loss rotor, magnetic fields on an order of magnitude higher than conventional machines, and a novel coil suspension and torque transfer system with tensioned fibers that cut the cryogenic heat-load by a factor of 10 to eliminate the need for external coolers. This design could enable a 10 MW, 3000 RPM aircraft propulsion motor weighing less than 250 kilograms that rejects up to 10 times less total heat to the ambient environment—achieving more than 99% efficiency.

See https://mechse.illinois.edu/news/45284 and https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/join-us-hinetics/?trackingId=MNdNJFW64n1BiZE5JNfqqg%3D%3D from which this piece was excerpted.

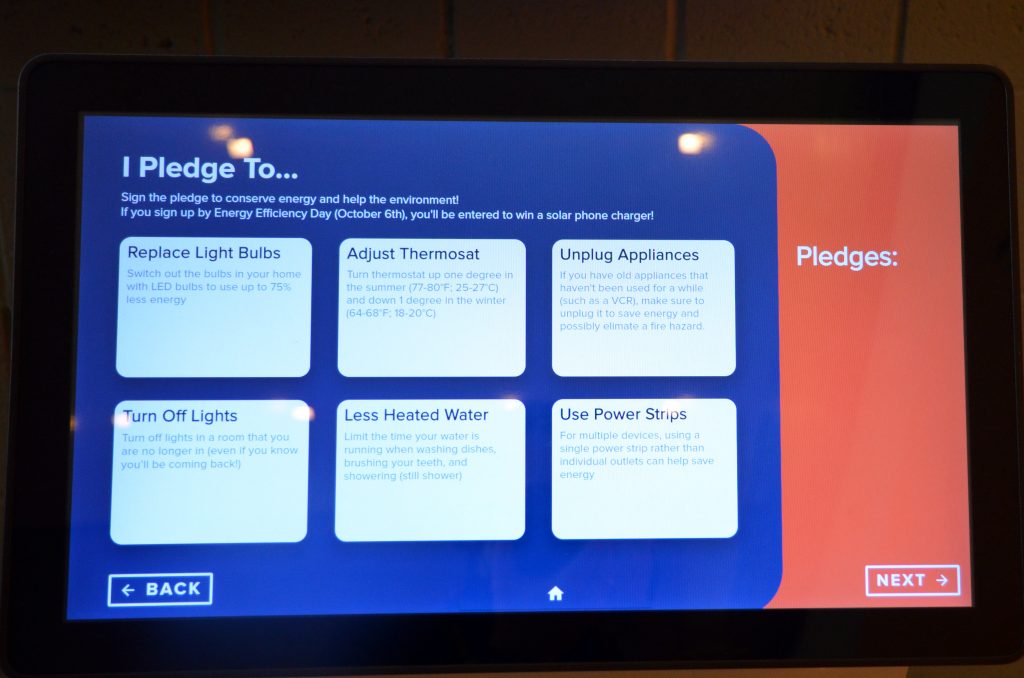

ECEB Lobby Energy Display: 0-Net Energy, Learning about Energy Efficiency, and Solar Phone Charger Drawing

The UIUC Student Sustainability Committee funded an energy display in the ECEB lobby to accomplish three goals. The first uses kiosks to teach students, faculty and campus visitors about energy use while presenting relatable and significant ways they can reduce energy-consumption patterns. The second is to show on a large screen energy being produced by the ECEB solar array, energy being used by ECEB, and ECEB’s allotment from Solar Farm 2 to reach zero net energy. The third is to demonstrate ECEB’s energy efficiencies and document its progress toward certification as the first zero-net energy building on campus.

To achieve the first goal, two touch-activated kiosks were installed and programmed identically for Engineering Open House 2021 https://ecebenergykiosk.web.illinois.edu/ by a Computer Science RSO headed by undergraduates Mitchell Bifeld and Smit Purohit. Kiosk visitors choose from several options and pledge to save energy. Their names are entered into random drawings twice a year: Energy Efficiency Day in October, and Earth Day in April. The first solar phone charger was awarded to Elaine Minghui Wang. Joyce Mast is handing her the charger.

Enough Power for EVs?

“With the rush to move to all electric vehicles, have the electric power generation companies been consulted? With all of the coal fired power plants being phased out, and no new nuclear plants coming online, will wind and solar be able to pick up the load? Worst case is we are building another bottle-neck that could raise utility rates for all of us, and make electric vehicles much more expensive.” Question from Tom’s Mailbag from the News-Gazette, February 4. 2021.

“It is a little hard to call it a ‘rush,’” said Phil Krein, a professor emeritus at the Grainger Center for Electric Machinery and Electromechanics at the University of Illinois. “The research community, transportation industry, and electric power industry have been engaged intensively on this issue over the past 25 years or so. Our regional utility, Ameren, is taking a leadership role.”

“In Illinois the growth in wind and solar electricity sources is far outpacing the growth in load from electric transportation,” Krein said. “The Federal Highway Administration’s 2016 Highway Statistics Report indicates about 10 million cars and trucks registered in Illinois. A transition of a few million of these to electrical energy is well within projected resource growth.”

“There’s plenty of generating capacity in Illinois and the Midwest to meet the demand,” he said. “And utility companies will incentivize consumers charging electric vehicles at times when power demand is lower.”

“Some will charge at night, some will charge at work. But the economic incentives will be such that it will tend to spread (demand) out,” said Krein. “They already have some of those rates in place.”

“A million (electric vehicles) is only 10 percent (of vehicles on the road in Illinois). It might get dicey when you get to 50 or 60 percent but by that time we should have our act together in many other ways as well. All the studies have shown that at 10 percent the impact on the grid is pretty minimal.”

“Illinois is better off than other states for a few reasons,” he said.

“Number one, despite their age and issues, we have a substantial nuclear power base. That’s a positive. Second is that although we don’t have the kind of wind resources that North Dakota or Nebraska have, we’ve got good wind resources and good solar resources. The other thing is that Illinois, in a sort of technical sense, is in the middle of the power grid and power flows through Illinois and we have really strong interconnections to resources. So when things go wrong we can be buying power from Tennessee and Indiana and Michigan and wherever.”

See TOM KACICH kacich@news-gazette.com from which this piece was excerpted.

ECE Researchers Part of $25 Million Grid-Integration Technology Consortium

Professor Alejandro Domínguez-García (right) in their research lab

Illinois ECE Professor Alejandro Domínguez-García and Research Engineer Olaolu Ajala are part of a $25 million Department of Energy-funded consortium that is addressing the reliability challenges involved in integrating more solar and wind energy onto the nation’s electric grid.

The Universal Interoperability for Grid-Forming Inverters (UNIFI) consortium brings together leading researchers from more than 40 university, industry, and utility organizations to evaluate and design grid-forming inverter solutions that will enable the seamless integration of inverter-based renewable resources while ensuring the grid’s stability and reliability.

“What we aim to do is figure out how to operate the power grid with a very large amount of renewable-based generation instead of using fossil fuel generating units,” said Alejandro. “The technology we need to use to achieve that is very different from the technology we currently have in the grid for generating power.” Alejandro and Olaolu will apply their expertise in control algorithm design, modeling, and simulation, to ensure that a future renewable-based system operates reliably.

“You don’t have the luxury to [validate your designs] in a real power system because it is already in operation,” Olaolu added. Instead, the Illinois researchers will perform testing and validation of their algorithms in a hardware-in-the-loop emulation environment, a sophisticated simulation technique of a real system that has been used by the automotive and aircraft industries for years. They’ll also examine how to scale their emulation schemes to large-scale power grids.

UNIFI is led by the National Renewable Energy Lab, the University of Washington, and the Electric Power Research Institute.

See 12/6/2021 article by Laura Schmitt from which this piece was excerpted: https://ece.illinois.edu/newsroom/news/43593#:~:text=Illinois ECE Professor Alejandro Dominguez-Garcia and Research Engineer and wind energy into the nation’s electric grid.

Banerjee Named Fellow of Center for Advanced Study

Professor Arijit Banerjee has been named Fellow of the Center or Advanced Study, providing one semester of release time for creative work during the 2022-23 school year. The announcement was made during the Board of Trustees Meeting on January 20, 2022. He plans to further his research on robots with a flexible spine.

Haran Named Grainger CEME Endowed Director’s Chair and Director of POETS

On March 2, 2022, Professor Kiruba Haran was invested as the Grainger Endowed Director’s Chair in Electric Machinery and Electromechanics, and on January 7, 2022, he was named new Director of the Center for Power Optimization of Electro-Thermal Systems (POETS) in the Grainger College of Engineering.

Professor Haran has taken over leadership of the Grainger Center for Electric Machinery and Electromechanics (CEME) from founder and former director Professor Emeritus Philip Krein. In moving from Associate Director to Director, he is exchanging roles with Professor Krein, who is continuing his research in electrified transportation.

As POETS director, Professor Haran is stepping into the role of former Mechanical Sciences and Engineering Director Andrew Alleyne, recently appointed Dean of the College of Engineering and Sciences at the University of Minnesota. Professor Alleyne secured an $18.5M grant from the National Science Foundation in 2015 to found POETS, “a key enabler in providing an increase in power density through advanced technology and workforce development, considering both the electrical and thermal systems from initial design concept and optimization through actual deployment in fielded vehicle testbeds. The goal is to break down the silos between different disciplines to co-design and co-operate these power-dense electro-thermal systems.”

College of Engineering Dean Rashid Bashir stated, “Professor Haran will provide leadership for the POETS Center at the college level. He will advance the vision and mission of the center to raise the college leadership profile, nationally and internationally, in the areas of electrical and thermal systems. He has been a key faculty investigator in the POETS Center; thus, he has a vision and direct experience to lead it to the next level.”

For more information on the POETS Consortium, see https://poets-erc.org/ and on this appointment, see https://mechse.illinois.edu/news/44650 from which this article was excerpted.