Race to Zero

A group of around 25 Illinois Solar Decathlon students began meeting in September 2017 to prepare a submission to the Race to Zero Competition hosted by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), a subsidiary of the U.S. Department of Energy. This competition is for college student teams to develop a building design that produces more energy than it uses. Construction drawings and a 40-page report outline and describe the proposal. About 88 teams applied for 40 competitive spots. The U of I team was one of eight out of 18 teams chosen to compete in their selected area.

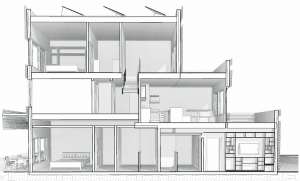

Team members were from six departments: Architecture – to handle building shape, narrative and passive design strategies – they designed an inexpensive, easily constructed structural system with tight thermal performance; ECE students addressed the PV array, taking in account solar tilt angles, cost-efficient panels, high-efficiency inverters, and affordability; Civil and Mechanical students determined the best thermal comfort system (HVAC) for building size and orientation; Civil engineering students focused on building and site water usage, including plants to help with site water absorption and interior plumbing to reduce water and energy usage. A key feature was a tight plumbing wall that reduced heat loss and travel distance for water; Agricultural and Biological Engineering students made sure all building features were optimized for cost versus benefit and compiled energy usage and creation data to determine the building’s energy output. Together, this group simulated working on a real building project in the architecture, engineering and construction industry.

Because Race to Zero is theoretical, teams can choose from many building types, including residential and commercial, and decide on a project goal and associated narrative. The U of I team looked at urban sprawl in ten out of fifteen southern US cities, where the car is the primary mode of transportation and the average commute is 7.7 to 11 miles. “This sprawl is created due to haphazardly planned developments and is increasing car usage and traffic. As these cities grow, price bubbles are created in the most appealing neighborhoods…pushing out existing residents … The Team Illinois project, Micro-munity, focuses on exemplifying how locals can transition to a public transportation-based lifestyle and live denser. Living in a more urban and denser environment decreases housing costs and makes areas more affordable…Charlotte, North Carolina was chosen as the project community, because its location provides the perfect example of this issue. The city is growing fast, and consequently, public transit infrastructure is too. However, developers are still designing for the car-based lifestyle. This mindset must change to focus on pedestrians. Micro-munity … set[s] a precedent to influence and inform responsible development in the future of urban American neighborhoods.

…The team focused on encouraging an active site in as many ways as possible. The building features three separate rentable commercial spaces to encourage the community to utilize the center space. The commercial spaces will assist in shifting the local community center towards a more walkable area of the neighborhood. … A large public courtyard acts as a small park for locals. In conjunction with this green space, the units themselves have large terraces that provide additional outdoor space for families transitioning into a denser living style.”

In April 2018, after submitting the entire proposal, five students traveled to NREL to present the project to a panel of jurors knowledgeable in sustainable building. The team received feedback, experienced other teams’ work and benefited from a sustainable design career fair.

This was an extremely rewarding experience and encouraged team members to bond even more than they had over the past year working together. All members who are still on campus are involved with one of the three teams that the Illinois Solar Decathlon supports.